- |

User Links

When I Survey the Wondrous Cross

When I survey the wondrous cross (Watts)

Author: Isaac Watts (1707)Communion Songs

Published in 2032 hymnals

Printable scores: PDF, MusicXMLPlayable presentation: Lyrics only, lyrics + musicAudio files: MIDI, Recording

Representative Text

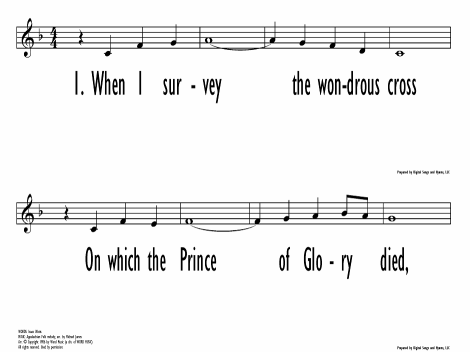

1 When I survey the wondrous cross

on which the Prince of glory died,

my richest gain I count but loss,

and pour contempt on all my pride.

2 Forbid it, Lord, that I should boast

save in the death of Christ, my God!

All the vain things that charm me most,

I sacrifice them through his blood.

3 See, from his head, his hands, his feet,

sorrow and love flow mingled down.

Did e'er such love and sorrow meet,

or thorns compose so rich a crown?

4 Were the whole realm of nature mine,

that were a present far too small.

Love so amazing, so divine,

demands my soul, my life, my all.

Psalter Hymnal, 1987

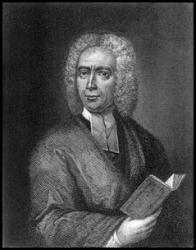

Author: Isaac Watts

Isaac Watts was the son of a schoolmaster, and was born in Southampton, July 17, 1674. He is said to have shown remarkable precocity in childhood, beginning the study of Latin, in his fourth year, and writing respectable verses at the age of seven. At the age of sixteen, he went to London to study in the Academy of the Rev. Thomas Rowe, an Independent minister. In 1698, he became assistant minister of the Independent Church, Berry St., London. In 1702, he became pastor. In 1712, he accepted an invitation to visit Sir Thomas Abney, at his residence of Abney Park, and at Sir Thomas' pressing request, made it his home for the remainder of his life. It was a residence most favourable for his health, and for the prosecution of his literary… Go to person page >

Isaac Watts was the son of a schoolmaster, and was born in Southampton, July 17, 1674. He is said to have shown remarkable precocity in childhood, beginning the study of Latin, in his fourth year, and writing respectable verses at the age of seven. At the age of sixteen, he went to London to study in the Academy of the Rev. Thomas Rowe, an Independent minister. In 1698, he became assistant minister of the Independent Church, Berry St., London. In 1702, he became pastor. In 1712, he accepted an invitation to visit Sir Thomas Abney, at his residence of Abney Park, and at Sir Thomas' pressing request, made it his home for the remainder of his life. It was a residence most favourable for his health, and for the prosecution of his literary… Go to person page >Text Information

| First Line: | When I survey the wondrous cross (Watts) |

| Title: | When I Survey the Wondrous Cross |

| Author: | Isaac Watts (1707) |

| Meter: | 8.8.8.8 |

| Language: | English |

| Notes: | French translation: "Quand je me tourne vers la croix" by Pauline Martin; German translation: "Schau ich dein Kreuz, o Heiland an" by Wilhelm Horkel; Portuguese translation: See "Olhando o lenho curcial"; Spanish translation: See "La cruz excelsa al contemplar" by W. T. T. Millham; Swahili translation: See "Msalaba nilipoona" |

| Copyright: | Public Domain |

| Liturgical Use: | Communion Songs |

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- (hymns)

- Year A, Epiphany Season, Fourth Sunday

This is recommended for Year A, Epiphany Season, Fourth Sunday by 2 hymnal lectionary indexes including Glory to God: the Presbyterian Hymnal #223. - Year A, Epiphany Season, Fifth Sunday

Related to 1 Corinthians 2 (NPM) - Year A, Lent, Palm Sunday

This is recommended for Year A, Lent, Palm Sunday by 3 hymnal lectionary indexes including Glory to God: the Presbyterian Hymnal #223 and Lift Up Your Hearts: psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs #175. - Year A, Holy Week season, Monday of Holy Week

This is recommended for Year A, Holy Week season, Monday of Holy Week by 2 hymnal lectionary indexes including Glory to God: the Presbyterian Hymnal #223. - Year A, Holy Week season, Good Friday

This is recommended for Year A, Holy Week season, Good Friday by 4 hymnal lectionary indexes including Glory to God: the Presbyterian Hymnal #223 and Lift Up Your Hearts: psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs #175. - Year A, Ordinary Time, Proper 6 (11)

This is recommended for Year A, Ordinary Time, Proper 6 (11) by 2 hymnal lectionary indexes including Glory to God: the Presbyterian Hymnal #223. - Year B, Lent, Palm Sunday

This is recommended for Year B, Lent, Palm Sunday by 2 hymnal lectionary indexes including Glory to God: the Presbyterian Hymnal #223. - Year B, Holy Week season, Monday of Holy Week

This is recommended for Year B, Holy Week season, Monday of Holy Week by 2 hymnal lectionary indexes including Glory to God: the Presbyterian Hymnal #223. - Year B, Holy Week season, Good Friday

This is recommended for Year B, Holy Week season, Good Friday by 4 hymnal lectionary indexes including Glory to God: the Presbyterian Hymnal #223 and Lift Up Your Hearts: psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs #175. - Year C, Lent, Fifth Sunday

This is recommended for Year C, Lent, Fifth Sunday by 4 hymnal lectionary indexes including Glory to God: the Presbyterian Hymnal #223 and Lift Up Your Hearts: psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs #175. - Year C, Holy Week season, Monday of Holy Week

This is recommended for Year C, Holy Week season, Monday of Holy Week by 2 hymnal lectionary indexes including Glory to God: the Presbyterian Hymnal #223. - Year C, Holy Week season, Good Friday

This is recommended for Year C, Holy Week season, Good Friday by 4 hymnal lectionary indexes including Glory to God: the Presbyterian Hymnal #223 and Lift Up Your Hearts: psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs #175. - Year C, Ordinary Time, Proper 9 (14)

This is recommended for Year C, Ordinary Time, Proper 9 (14) by 2 hymnal lectionary indexes including Glory to God: the Presbyterian Hymnal #223 and Lift Up Your Hearts: psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs #175. - Year C, Ordinary Time, Proper 18 (23)

This is recommended for Year C, Ordinary Time, Proper 18 (23) by 3 hymnal lectionary indexes including Glory to God: the Presbyterian Hymnal #223.

Chinese

English

- 112 Familiar Hymns and Gospel Songs #82

- 50 Uncommon Songs: for partakers of the common salvation #45

- 52 Hymns of the Heart: with an appendix of favorite solos and choruses (Missionary and Church Extension Ed.) #36

- A Baptist Hymn Book, Designed Especially for the Regular Baptist Church and All Lovers of Truth #d852

- A Book of Worship for the Use of the Evangelical Lutheran Church ... of the Church of the Redeemer, Richmond, Virginia #d192

- A choice collection of popular songs with some standard hymns for young people's meetings (Silver and Gold No. 1) #d147

- A Choice Selection of Evangelical Hymns, from various authors: for the use of the English Evangelical Lutheran Church in New York #58

- A Choice Selection of Hymns and Spiritual Songs for the use of the Baptist Church and all lovers of song #140

- A Choice Selection of Psalms, Hymns and Spiritual Songs for the use of Christians #291

- A Church Hymn Book: for the use of congregations of the United Church of England and Ireland #55 10 shown out of 1381

French

German

Spanish

Welsh

Notes

One Sunday afternoon the young Isaac Watts (1674-1748) was complaining about the deplorable hymns that were sung at church. At that time, metered renditions of the Psalms were intoned by a cantor and then repeated (none too fervently, Watts would add) by the congregation. His father, the pastor of the church, rebuked him with "I'd like to see you write something better!" As legend has it, Isaac retired to his room and appeared several hours later with his first hymn, and it was enthusiastically received at the Sunday evening service the same night.

Although the tale probably is more legend than fact, it does illustrate the point that the songs of the church need constant infusion of new life, of new generation's praises. With over 600 hymns to his credit--many of them classics like "When I Survey the Wondrous Cross"--Isaac Watts has rightfully earned the title, "the father of English hymnody." This hymn, which is known as Watts' crowning achievement, was first published in this "Hymns and Spiritual Songs, 1707" and was matched with such tunes as "Tombstone" and an altered version of Tallis' canon called "St. Lukes." For many years it was sung to "Rockingham" by Edward Miller, the son of a stone mason who ran away from home to become a musician, later becoming a flutist in Handel's orchestra. In recent history the hymn text has settled in with Lowell Mason's "Hamburg," an adaptation of a five note (count them!) plainchant melody. Besides writing thousands of hymn tunes he was a church choir director, the president of Boston's Handel and Haydn Society, and a leading figure in music education.

Though "When I Survey the Wondrous Cross" was intended originally as a communion hymn, it gives us plenty to contemplate during Lent as our focus is on the cross Christ. The hymn is said to be based on Galatians 6:14 (May I never boast except in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, through which the world has been crucified to me, and I to the world.) which is evident in a verse that Watts' eliminated from later editions of the hymn:

His dying crimson, like a robe,

Spreads o'er his body on the tree;

Then am I dead to all the globe,

And all the globe is dead to me.

Perhaps Watts eliminated this verse in order to focus more attention on our response to Christ's crucifixion than the crucifixion itself. Notice how he starts with contemplation of the cross and the fact that all our worldly achievements and possessions pale in comparison. Next he shows that Christ went to the cross out of love for us. In the most powerful image of the hymn, he affirms the deity of the suffering Christ with the brilliant juxtaposition: "Did e'er such love and sorrow meet, Or thorns compose so rich a crown?" And the last verse shows that the only proper response to this amazing love is complete devotion. --Greg Scheer, 1997

----------------------

When I survey the wondrous Cross. I. Watts. [Good Friday.] This, the most popular and widely used of Watts's hymns, appeared in his Hymns and Spiritual Songs, 1707, and in the enlarged edition 1709, as:—

"Crucifixion to the World, by the Cross of Christ. Gal. vi. 14.

1. “When I survey the wond'rous Croƒs

On which the Prince of Glory dy'd,

My richest gain I count but Loƒs,

And pour Contempt on all my Pride.2. ”Forbid it, Lord, that I ƒhould boaƒt

Save in the Death of Christ my God;

All the vain Things that charm me moƒt,

I ƒacrifice them to his Blood,3. "See from his Head, his Hands, his Feet,

Sorrow and Love flow mingled down!

Did e'er ƒuch Love and Sorrow meet,

Or Thorns compose ƒo rich a Crown!4. "[His dying Crimƒon, like a Robe,

Spreads o'er his Body on the Tree;

Then am I dead to all the Globe,

And all the Globe is dead to me.]5. "Were the whole Realm of Nature mine,

That were a Preƒent far too ƒmall;

Love ƒo amazing, ƒo divine,

Demands my Soul, my Life, my All."

The first to popularize the four-stanza form of the hymn (stanza iv. being omitted) was G. Whitefield in the 1757 Supplement to his Collection of Hymns. It came rapidly into general use. In common with most of the older hymns a few alterations have crept into the text, and in some instances have been received with favour by modern compilers. These include:

Stanza ii. 1. 2. "Save in the Cross," Madan, 1760.

Stanza iii. 1. 2. "Love flow mingling," Salisbury, 1857.

Stanza iv. 1. 2. “That were a tribute," Cotterill, 1819,

Stanza iv. 1. 2. "That were an offering," Stowell, 1831.

The most extensive mutilations of the text were made by T. Cotterill in his Selection 1819; E. Bickersteth in his Christian Psalmod, 1833; W. J. Hall in his Mitre Hymn Book 1836 ; J. Keble in the Salisbury Hymn Book 1857; and T. Darling in his Hymns for the Church of England, 1857. Although Mr. Darling's text was the only one condemned by Lord Selborne in his English Church Hymnody at the York Church Congress in 1866, the mutilations by others were equally bad, and would have justified him in saying of them all, as he did of Mr. Darling's text in particular:—

“There is just enough of Watts left here to remind one of Horace's saying, that you may know the remains of a poet even, when he is torn to pieces."

In the 1857 Appendix to Murray’s Hymnal; in the Salisbury Hymn Book 1857; in Hymns Ancient & Modern, 1861 and 1875; in the Hymnary, 1872; and in one or two others a doxology has been added, but this practice has not been received with general favour. One of the most curious examples of a hymn turned upside down, and mutilated in addition, is Basil Woodd's version of this hymn beginning "Arise, my soul, with wonder see," in his undated Psalms of David, &c. (circa 1810), No. 198.

The four-stanza form of this hymn has been translated into numerous languages and dialects. The renderings into Latin include: “Quando admirandam Crucem," by R. Bingham in his Hymno. Christiana Latina, 1871; and "Mirabilem videns Crucem," by H. M. Macgill in his Songs of the Christian Creed and Life, 1876. The five-stanza form of the text as in Hymns Ancient & Modern (stanza v. being by the compilers) is translated in Bishop Wordsworth's (St. Andrews) Series Collectarum, 1890, as "Cum miram intueor, de qua Praestantior omni." In popularity and use in all English speaking countries, in its original or in a slightly altered form, this hymn is one of the four which stand at the head of all hymns in the English language. The remaining three are, "Awake, my soul, and with the sun;" "Hark! the herald angels sing;" and "Rock of Ages, cleft for me."

--John Julian, Dictionary of Hymnology (1907)

Tune

HAMBURGLowell Mason (PHH 96) composed HAMBURG (named after the German city) in 1824. The tune was published in the 1825 edition of Mason's Handel and Haydn Society Collection of Church Music. Mason indicated that the tune was based on a chant in the first Gregorian tone. HAMBURG is a very simple tune with…

ROCKINGHAM (Miller)

Edward Miller (b. Norwich, England, 1735; d. Doncaster, Yorkshire, England, 1807) adapted ROCKINGHAM from an earlier tune, TUNEBRIDGE, which had been published in Aaron Williams's A Second Supplement to Psalmody in Miniature (c. 1780). ROCKINGHAM has long associations in Great Britain and North Amer…

EUCHARIST (Woodbury)

For Leaders

The Lutheran Hymnal Handbook includes this little narrative about the hymn “When I Survey the Wondrous Cross:” “With regard to the practical application of the final stanza, Father Ignatius of St. Edmund’s Church in London is reported to have blurted to his congregation: ‘Well, I’m surprised to hear you sing that. Do you know that altogether you put only fifteen shillings in the collection bag this morning?’”,

While Watts might not have been talking explicitly about money in the last line of his text, there is the expectation that we dedicate ourselves entirely to God, for God demands not just a piece of who we are, but “our soul, our life, our all.” This can be an incredibly difficult line to sing with any sense of honesty. Devotional author Jerry Jenkins writes in his book Hymns for Personal Devotions, “Perhaps it’s the distance between where Watts encourages me to be and where I truly am that makes this hymn so hard to sing. It’s a lofty and worthy spiritual goal to say that ‘Love so amazing, so divine, demands my soul, my life, my all,’ but how short I fall!” (Jenkins, 44). And so as we sing this hymn of love and awe, we must sing it with a prayer in our hearts, asking God to enable us each day to live our life wholly for him.

Text:

Watts’ original text, published in 1707, consisted of five verses. He later took out his original fourth verse, which read,

His dying crimson, like a robe,

Spreads o’er his body on the tree;

Then am I dead to all the globe,

And all the globe is dead to me.

Greg Scheer speculates that perhaps Watts eliminated this verse to focus our attention on our own response to Christ’s crucifixion rather than the actual event itself. This would make sense since Watts wrote the text for a collection of hymns for the Lord’s Supper, an act in which we remember and respond with gratitude to Christ’s sacrifice for us.

Apart from this verse being omitted, not much else has changed in this text, and for good reason: the Psalter Hymnal Handbook writes that “Watts’ profound and awe-inspiring words provide an excellent example of how a hymn text by a fine writer can pack a great amount of systematic theology into a few memorable lines.” The only slight differences you can find between texts are changes of a few words, such as “present/tribute/offering” in the fourth verse.

Tune:

The first tune used to accompany Wesley’s text was HAMBURG, composed by Lowell Mason in 1824, and based on a chant in the first Gregorian tone. The whole melody only consists of five notes. Some argue that this allows us to focus entirely on the text. Others, like hymnologist Erik Routley, wrote that “the attempt to square up Gregorian chant into a regular 4/2 rhythm and to harmonize it with straight chords was fatal to the enterprise…as a hymn tune it has no merit whatever and claims none” (Westermeyer, Let the People Sing, 299). Westermeyer adds that while this tune might be “dull to the analyst,” it is often much appreciated and loved by the congregation.

Another tune option is ROCKINGHAM, but this also comes under critique. Westermeyer quotes Robert Bridges who “thought the ‘grandeur’ of Watts’ text was ‘obscured’ by this melody” (Let the People Sing, 197). It is perhaps too jaunty for this hymn of awe. Thus, another tune option is O WALY WALY, a traditional English melody which fits the text rather well. Greg Scheer has an arrangement of this tune for strings and piano that he’s used for other texts such as “As Moses Raised the Serpent Up” and “O Blessed Spring.”

HAMBURG is the most commonly used tune, however, and there are a number of good arrangements of the tune. A well-known medley was arranged by Chris Tomlin and combines Watts’ text with a refrain, “O the wonderful cross, o the wonderful cross, bids me come and die and find that I may truly live.” When using this medley, build into those refrains instrumentally and pull back on each of the verses.

When/Why/How:

Originally written for The Lord’s Supper, this hymn can be used at this point in a service throughout the year. Our remembrance of Christ’s death and resurrection through Watts’ text also makes this a much-loved and often-used hymn for Lent, especially Holy Week. On Good Friday, consider singing it at the very end of a Tenebrae or Good Friday service as a reflection on the rest of the service and the events of Holy Week.

Suggested music:

- Joncas, Jan Michael. Adoramus Te - for SAB Choir, with Guitar and Organ parts, the text of "When I Survey" to a tune composed by Joncas

- Tomlin, Chris. The Wonderful Cross - for Choir

- Hopson, Hal H. When I Survey the Wondrous Cross - Viola or Cello and Piano duet

- Larson, Lloyd. The Cross (A Hymn Medley for Orchestra)

- Cherwien, David Lamb of God-Five Lenten Hymn Settings - for Organ

- Hopson, Hal H. The Creative Use of the Piano in Worship

- Keene, Karen. When I Survey the Wondrous Cross - the tune ROCKINGHAM, for Organ

Laura de Jong, Hymnary.org

Timeline

Arrangements

Media

Methodist Tune Book: a collection of tunes adapted to the Methodist Hymn book #8

- MusicXML (XML)

Methodist Tune Book: a collection of tunes adapted to the Methodist Hymn book #14

- MusicXML (XML)

Psalter Hymnal (Gray) #384

Small Church Music #171

- PDF Score (PDF)

The United Methodist Hymnal #298

The United Methodist Hymnal #299

- MIDI file from Bethany Hymns: A compilation of Choice Songs and Hymns #52

- MIDI file from Baptist Hymnal 1991 #144

- Audio recording from Baptist Hymnal 1991 #144

- MIDI file from Baptist Hymnal 1991 #144

- MIDI file from Beulah Songs: a choice collection of popular hymns and music, new and old. Especially adapted to camp meetings, prayer and conference meetings, family worship, and all other assemblies... #106

- Audio recording from Catholic Book of Worship III #382

- MIDI file from Crowning Day No. 2 #223

- MIDI file from Christian Endeavor Hymns #120

- Audio recording from Celebrating Grace Hymnal #186

- MIDI file from The Cyber Hymnal #7370

- Audio recording from The Hymnal 1982: according to the use of the Episcopal Church #474

- Audio recording from Evangelical Lutheran Worship #803

- MIDI file from Favorites Number 1: A Collection of Gospel Songs #45

- MIDI file from The Finest of the Wheat: hymns new and old, for missionary and revival meetings, and sabbath-schools #38

- MIDI file from Gloria Deo: a Collection of Hymns and Tunes for Public Worship in all Departments of the Church #156

- Audio recording from Glory to God: the Presbyterian Hymnal #223

- Audio recording from Glory to God: the Presbyterian Hymnal #224

- MIDI file from Hymns of the Kingdom: for use in religious meetings #44

- MIDI file from The Junior Hymnal, Containing Sunday School and Luther League Liturgy and Hymns for the Sunday School #138

- Audio recording from Lutheran Service Book #426

- Audio recording from Lift Up Your Hearts: psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs #175

- Audio recording from Lift Up Your Hearts: psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs #175

- Audio recording from Lift Up Your Hearts: psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs #175

- Audio recording from Lift Up Your Hearts: psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs #175

- Audio recording from Methodist Tune Book: a collection of tunes adapted to the Methodist Hymn book #8

- Audio recording from Methodist Tune Book: a collection of tunes adapted to the Methodist Hymn book #14

- Audio recording from The New Century Hymnal #224

- MIDI file from Northfield Hymnal No. 3 #362

- MIDI file from The Old Story in Song Number Two #146

- Audio recording from Psalter Hymnal (Gray) #384

- MIDI file from Psalter Hymnal (Gray) #384

- MIDI file from Psalter Hymnal (Gray) #384

- Audio recording from Revival Hymns and Choruses #551

- Audio recording from Small Church Music #170

- Audio recording from Small Church Music #170

- Audio recording from Small Church Music #171

- Audio recording from Small Church Music #171

- Audio recording from Small Church Music #172

- Audio recording from Small Church Music #172

- MIDI file from Songs of Help: for the Sunday school, evangelistic and church services #146

- Audio recording from Trinity Hymnal (Rev. ed.) #252

- MIDI file from Tabernacle Hymns: No. 2 #195

- MIDI file from Triumphant Songs No.2 #106

- MIDI file from The United Methodist Hymnal #298

- Audio recording from The United Methodist Hymnal #298

- MIDI file from The United Methodist Hymnal #299

- Audio recording from The United Methodist Hymnal #299

- MIDI file from Worship and Rejoice #261

- MIDI file from Worship in Song: A Friends Hymnal #112

- Audio recording from Worship (4th ed.) #494

My Starred Hymns

My Starred Hymns